If the Kenyan map was shaped like the average woman’s body, Lokitaung and Mandera would be the shoulders. It would curve to the tapering waist at Mt. Elgon then broaden to the left hip near Migori. Oloitokitok then, would be the left knee.

Oloitokitok lies on the toes of the majestic Mt. Kilimanjaro on the leeward side. The road leading here is lean, dark and smooth as Nutella. Maasais are the predominant tribe, a pastoralist community that lives in ‘Manyattas ’; a homestead made up of about 10 mud and dung huts. They are a most handsome tribe, gangly, lean and dark. Majority of them don traditional regalia, more often in the villages than in the main shopping center. The men wear fabrics neatly tied around their waists and another casually draped on their shoulders like in those high end fashion catwalks. A club is usually dexterously tied to the waist fabric. Simply but ominously, just in case of an encounter with anyone annoying. Ladies have ‘Kangas’ tied on their chest above the breasts while another is tied on the neck like a cape. Like they are all super heroines. Everyone is slim. No one cares about facebook likes. None of the food is fast.

Livestock grazes in the bordering game reserve, the Amboseli National Park and there is an air of mutual respect between the lions and the herdsmen. They rarely eat plants. Doing so means poverty in this area and one would rather face malnutrition than be labeled as poor. When famine strikes, they migrate. To them, it is nature’s cull of the feeble and unlucky. But times are changing. Now, most of their children go to school, they save money in banks and are steadily buying into the mixed farming idea.

The Project Survival Media team arrived here from Nairobi, 180 miles away, just as the sun set behind Kibo peak. That view! Good heavens. That view was most stupendous! Like a tabletop covered with a crisp whitecloth that was snow. The way gods dine. It disappeared fast as the night set in. We woke up early to hear God yawning with the early birds, his breath giving a misty look to the town; cloak and dagger story. That was the sound of the morning breeze blanketing a Lion’s roar and an elephant’s trumpet that followed about ten minutes later. These sounds are to an Oloitokitokian what an iPhone ringtone is to a city resident.

The three of us stand outside a shop that is selling solar lanterns. Our film maker John smiles at two young adolescent Maasai ladies. They giggle shyly unburdened and one actually cat calls him then shyly runs to the other side of the road and disappears into the market place. Our guide Ben who doubles up as the community trainer on solar systems goes into the shop then leaves, behind him is a gangly man. I say ‘Ero’ and extend my hand to him. He has a combat jacket a top of his regalia. He takes it, shakes it firmly and says ‘suba’. He is the chief of Iltilal. We have to leave now, the chief explains as he takes long strides towards his motorbike. Ben does the same and John and I jump into the car and follow them.

After two km on the main highway, we branch off the tarmac towards Iltilal village. It’s as dusty as it will be during Armageddon. At some point I completely lose the chief as a herd of more than 100 cattle crosses the road infront of me leaving a huge cloud of dust. A boy of about 14 walks behind them and shouts Ero at us. He waves and grins. We wave. The cattle’s’ tails wave too. Everything here waves. His eyes shine of something I imagined is valor. After all he might be the only one among us who has encountered a lion repeatedly and not peed on himself.

We catch up with the chief eventually and follow him into a homestead where a group of women have gathered to learn about solar systems. Here’s the deal: the number of churches in this area is almost inexistent and following colonial history, so are schools. Oloitokitok did not have that rich green seduction of the highlands and thus as the missionaries smuggled in psalms and cash crops in the usual gaucheness, it was left pristine. It is dry. And brown as beans. At first sight the area neatly encapsulates the most told African story; of anthropomorphism and bad news. But stay for a minute too long and you’ll notice Oloitokitok oozes something else; synergy, culture and optimism.

With about one school per a radius of about ten km, no electricity and water systems in an arid area bordering wild animals, it’s amazing that the community has some knowledge on the ill effects of using fossil fuels like Kerosene as is the usual alternative in remote Kenya. Furthermore, they are increasingly aware that wood fuel and deforestation is devastating their already fragile land. Therefore they refuse to be footnotes of their own story. The small meeting arranged by the women, the chief, the trainer from the solar shop and a women trust fund radiates a cohesion, a common beat that we met all over Oloitokitok. They felt a need for local indigenous solutions to their problems.

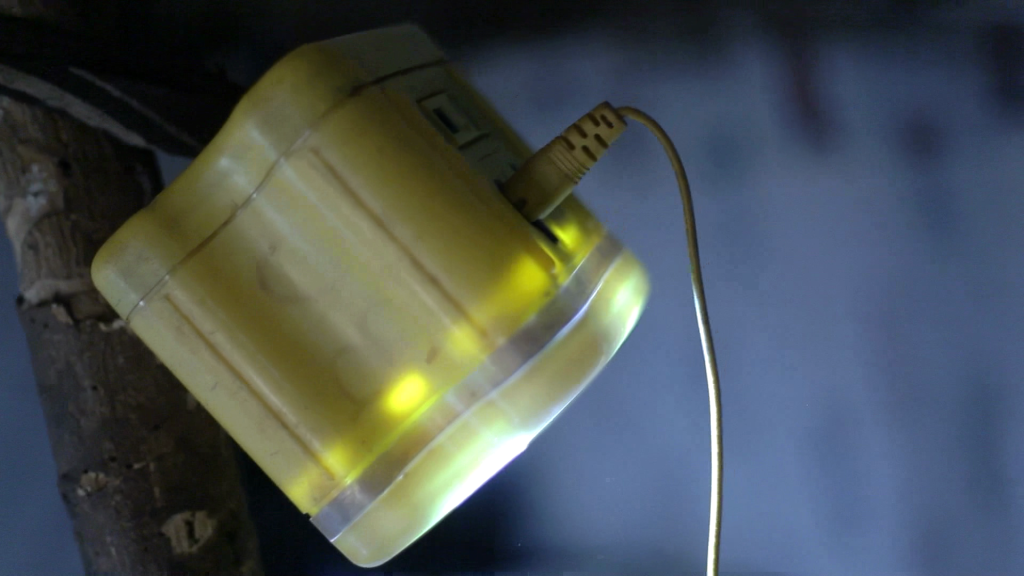

I watch as Margaret tells her story to the rest of the women. She had bought a solar system 3 years earlier as she’d gotten tired of the 20km walk to town to have her phone charged. Such hard-earned charge cannot be wasted on things like pray, tweeting. Her daughter had suffered chest pains from the kerosene fumes too and she’d talked to her husband after which they’d agreed to get a solar systems. She now saves: time and energy, money that would have been spend on kerosene lamps, wood for fuel, and her family’s health is now way better than before. Another lady talks of how it would help if she got a solar system to keep away elephants which had fallen into the habit of passing through her homestead. She’d been using dry branches which she lit and left outside but they died off pretty quickly and they didn’t produce as much light. So Ben called the Women’s Trust Fund office and arranged for her to pick up a solar system from the shop through a loan program that the fund offers.

Elang’ata Enkima School was 80km of the silently-portentous-dry-weather road away. The small trenches on the road formed by rainwater looked okay, but the vehicle shook too much if I drove too slowly and the tires kept sliding towards the ditches on the sides if I went too fast. Here’s the trick to traveling through Africa. There are no expectations. That ‘Safari book’ that you’ve been reading to help you plan your vacation, toss it.You will never reach your destination on time. There will be black outs as you attempt to print out your itinerary, rains will leave you stuck in a remote village that Google maps cannot find. Enjoy it and you’ll stay content.

It was going to be a one hour drive. We stopped to give a lift to two charming old Maasai ladies. About 5 minutes later, John tried to say something and I leaned over to hear him over the vehicle’s engine. Now, in the Maasai culture, it is taboo for a woman to interact freely with men let alone lean over closely in public. My leaning therefore shocked the ladies. Their eyes shot daggers and they swore under their breaths at the moral decadency. I was unaware of the buzz I created behind me. Ben was too fascinated by this that he forgot to warn me of the impending black spot on the road. That is how we ended up in a ditch with two flat tires.

Luckily, we got the flats a short distance from a Maasai Manyatta. A group of them hurriedly came to our aid, lifting the car back to the road, calling the village mechanic and although it took time to have an extra tire delivered to us on a motorbike, we finally reached the school 3 hours later.

At the school, there were no signs of large aid organisations advertising their foundations to kick out AIDS, or malnutrition, or illiteracy as is usual in many of these dry areas. Instead, on the roof, solar panels lay proudly shattering the sun’s rays, absorbing them and storing up their energy for evening studies. A group of children ran by me, giggling on their way to having lunch and two thoughts struck me. One was, ergonomically the poorer the children, the more beautiful their dreams seemed; the second was that what I thought were the challenges to achieving their dreams was simply a way of life for them. I knew I had to visit with them in their homes and find the source of their optimism if at all, I could.

The solar systems had been donated by the Women’s Trust Fund and they were approached by the teachers and parents led by their chief. Lillian Kasee was a pupil in grade 8 waiting to go to highschool. Without a library in the school, or a television, or a smart phone, the most envied position in her village was that of a teacher. She wanted to be one. She had her solar lantern now and after the eight km walk home, she could study hard without constant eye problems caused by fumes emitted by the hand kerosene lamps she earlier used. Furthermore, she didn’t have to collect wood fuel for lighting her mother’s hut. The same scenario repeated itself in all the forty homesteads of all the pupils in grade 8 studying to get into high school.

The synergy that flowed throughout the village from the chief, to the women groups, the Women’s Trust Fund, to the parents, teachers and pupils in the school opened our eyes to an optimistic web. To a story that created a climate change solution that enabled the young people do such basic things like studying, ergo facilitating their education and paving a detailed way to solutions in the future. With the education, community projects, synergy and optimism, people of Oloitokitok are on the road map to indigenous solutions not only for climate change but for global literacy and poverty.

For us, the few days spent in Oloitokitok were worth weeks spent anywhere else.

BY WAMBUI GICHOBI